Then there are the “Maya Codices,” with the sacred laws of the Mayan civilisation. I gather these remained largely untranslated for centuries due to the Catholic church wilfully destroying so many of them – something that evokes DVC’s historical scenario. Knowledge of the Maya civilisation, the subject of Mel Gibson’s film Apocalypto, is based largely on the few surviving Maya Codices, known as The Madrid Codex, The Dresden Codex, and The Paris Codex. The Bible itself is taken from a codex, the Codex Amiatinus, earliest surviving manuscript on from which the Latin Vulgate version was taken and thought based on another codex, the Codex Grandior of Cassiodorus as well as the writings of St. Jerome. Called by some "the finest book in the world", its two-column calligraphy is a product of the Celtic monastic movement, being a work commissioned in 692 by Bede’s mentor Abbot Ceolfrid, founder of Wearmouth Abbey and its calligraphy school. (A gift copy of this work is still used by the Pope as his own personal Bible.)

The term codex is also now being applied to the latest theory about 'the longest running treasure hunt in the world', the Oak Island Money Pit, a mystery sometimes connected to the Templars, where the landscape clues are referred to as a First Nations or native American equivalent to a codex. The Da Vinci Code itself uses the term as an “alphabet-inspired code breaking device.”

Post-DVC, it seems to be coming into more general usage due to novels, TV shows and games using the title, which offers the appeal of a close variant on the already-overused word Code. There’s Douglas Preston’s The Codex, which seems to be a family-inheritance treasure hunt related to Mayan codices that may hold the cure to cancer. There’s plain Codex (no “The”) by Lev Grossman, a “cerebral thriller”, which Amazon says deals with mediaeval literature and a related computer game, thus offering “an added twist for the technophile” in “the emerging genre of literary history thrillers.” A series of novels (Celtika, The Iron Grail) from fantasy author Robert Holdstock (of Mythago Wood fame), is called The Merlin Codex, where the codex in question purports to be Merlin’s real story, his autobiography that he notionally left behind for posterity as a handwritten manuscript.There’s even a game show: Channel 4’s latest attempt to cater to the Da Vinci Code market this winter has been a Sunday-evening game show hosted by Tony Robinson, the actor who followed up playing Baldrick on BBC’s cult historical sitcom Blackadder by presenting history documentary series – C4’s long-running Time Team, and last year’s The Real Da Vinci Code (reviewed here earlier). C4’s Codex series involves a team locked in the British Museum at night and having to solve a set of riddles and puzzles about an ancient civilisation.

The C4 show uses ‘the codex’ to mean a cylinder containing a parchment scroll with a secret on it. In TDVC Dan Brown posited such a cylinder, which he named a cryptex, which had a combination-lock set of rotatable dials reminiscent of the German WWII Enigma machine. If you just broke it open, a glass vial would release the vinegar inside, turning the papyrus into mush, as happens in the end. I’ve always been suspicious about this. There’s an expression in British politics that today’s news is just tomorrow’s fish‘n chip wrapping. This derives from the fact that before the EU’s Codex Alimentarius was brought in to regulate British food, fish‘n chip shops used newspaper as insulation-wrapping. And even when the chips were so soaked in vinegar it penetrated right through, it did not eat away the newspaper but left the newsprint still visible. Now a palaeographer who was also suspicious of this plot device has done tests showing that vinegar will not dissolve, or even damage, ancient papyrus….. All that trouble, when anybody who got their hands on that cryptex over the centuries could’ve just whacked it open.

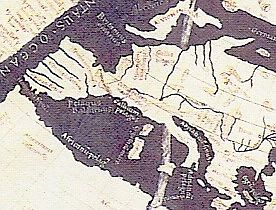

The C4 show uses ‘the codex’ to mean a cylinder containing a parchment scroll with a secret on it. In TDVC Dan Brown posited such a cylinder, which he named a cryptex, which had a combination-lock set of rotatable dials reminiscent of the German WWII Enigma machine. If you just broke it open, a glass vial would release the vinegar inside, turning the papyrus into mush, as happens in the end. I’ve always been suspicious about this. There’s an expression in British politics that today’s news is just tomorrow’s fish‘n chip wrapping. This derives from the fact that before the EU’s Codex Alimentarius was brought in to regulate British food, fish‘n chip shops used newspaper as insulation-wrapping. And even when the chips were so soaked in vinegar it penetrated right through, it did not eat away the newspaper but left the newsprint still visible. Now a palaeographer who was also suspicious of this plot device has done tests showing that vinegar will not dissolve, or even damage, ancient papyrus….. All that trouble, when anybody who got their hands on that cryptex over the centuries could’ve just whacked it open.Of course there are other codices which have never been found by historians, but which they presume existed as the now-lost sources of surviving early accounts. For example, as indicated in our earlier Ptolemy-map-as-codex item [image detail above], the earliest classical source of information about Britain likely comes from a now-lost periplous, and soon we will take a closer look at that mystery, for it holds a key to the puzzle which is the main subject of this blog.